Nanoparticles: when a tiny particle could mean a giant leap for breast cancer

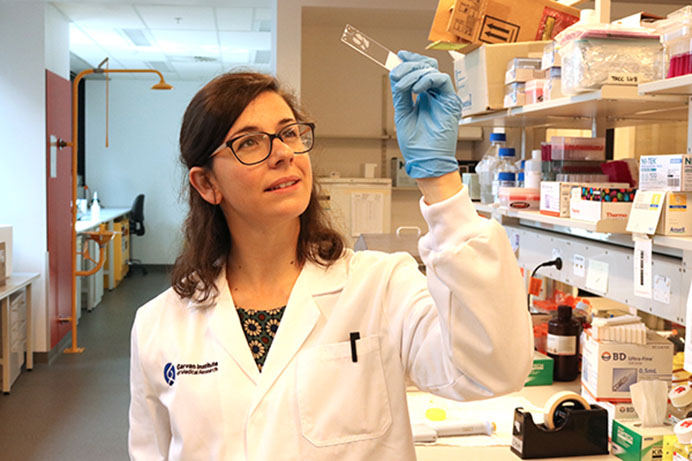

Early-career researcher Dr Elysse Filipe leverages novel engineering tool to enhance chemotherapy efficacy with hyper-targeted therapy

Chemotherapy is an inherently aggressive treatment to an even nastier issue. To help change the face of breast cancer treatment, Dr Elysse Filipe has been running an exciting, cutting-edge project at the Garvan Institute - in collaboration with the Applied Materials and Plasma Physics group from the University of Sydney and with the support of St Vincent's Clinic Foundation.

Chemotherapy is an inherently aggressive treatment to an even nastier issue. To help change the face of breast cancer treatment, Dr Elysse Filipe has been running an exciting, cutting-edge project at the Garvan Institute - in collaboration with the Applied Materials and Plasma Physics group from the University of Sydney and with the support of St Vincent's Clinic Foundation.

By combining nanoparticles with standard chemotherapy, she aims for what she calls the ‘Holy Grail’: hyper-targeted treatment. Today, chemotherapy spreads through a patient’s veins and affects all parts of the body that are not sick. Instead, Dr Filipe is working on a way to direct the drug straight to the cancer cell. To achieve this, she uses nanoparticles to carry a targeting agent that plays the role of a GPS, taking the drug exactly where it needs to go.

“By having these nanoparticles accumulate in the tumour, not only can we avoid all these side-effects caused by chemotherapy spreading throughout the whole body, but because it helps to increase the concentrations specifically in the tumours, we can reduce the dose that’s required and minimise damage to healthy tissues. That's the golden opportunity,” says Dr Filipe.

The cocktail Dr Filipe is testing combines three key components: the chemotherapy drug, a targeting agent, and an imaging agent (allowing her to see whether the drug has reached the tumour). Binding all those components into one single cocktail is no small feat, and this is where she brings something different to the bench.

The nanoparticles she uses are carbon-based, which have the very unique property of binding different components extremely easily and quickly, making it an ideal platform to bring together multiple functionalities (such as a drug and a targeting agent). She brought the wonders of this technology with her after her PhD at University of Sydney, where these carbon nanoparticles were first discovered and developed - and where she first became involved in the research project.

“I worked on these carbon nanoparticles during my PhD in Bioengineering, and now as a cancer biologist I can really see how to deploy them to their full potential for new therapies, particularly cancer therapies. It’s fascinating to go from developing a technology to actually applying it.”

The 2020 grant she received from St Vincent’s Clinic Foundation has been instrumental in getting the study up and running. The funding has also enabled her to gather preliminary data that is fundamental to apply for future grants.

“Without the grant, I would be a young researcher with a good idea. Thanks to the Foundation, I have an idea with strong data to back it up. It’s really given me a springboard.”

Since January, Dr Filipe has made some headways before COVID-19 put a halt to the study. First, in vitro tests in 3D have been particularly promising, revealing enhanced potency of the chemotherapy drug when bound to nanoparticles: with only half the dose compared to chemotherapy alone, the same amount of cancer cells are killed.

Finally, Dr Filipe has expanded the scope of her study, which originally focused on metastatic (spread) triple negative breast cancer, the most difficult subtype to treat due to the lack of targeted therapies. Driven by input from clinician A/Prof Elgene Lim, the team decided to open up the study’s framework.

“A/Prof Elgene Lim has been providing a clinical point of view to the study, which has been incredibly valuable. When we started discussing the framework, we were focusing on metastatic triple negative breast cancer and he made us look at the bigger picture: if we find a targeted therapy that can also reduce primary tumour growth, it could well be applied to all breast cancer patients.”

From then on, the team has been working with a double objective in mind. On one hand, improving survival rates for women with metastatic triple negative breast cancer, and on the other hand, offering life-changing treatment for women with primary breast cancer (cancer that has not spread).

Due to COVID-19, the next phase, which relies on in vivo tests, is on hold for the moment, but Dr Filipe hopes she can restart her work soon - and take the study to the next level.